US President Joe Biden’s visit to Belfast last week inevitably drew comparisons with key interventions made by fellow Democratic President Bill Clinton in the Northern Ireland Peace Process more than two decades ago.

Clinton’s three visits — in 1995, 1998 and 2000 — were widely viewed as being instrumental first in nudging unionists and republicans toward a deal, and then in keeping the 1998 Good Friday Agreement alive during the turbulent months and years after it was signed.

Observers in Belfast, Dublin and London, as well as interested parties further afield, hope that Biden’s visit will have a similarly galvanizing effect on politics in the province which, once again, appear to be deadlocked.

Biden, of course, lacks the pull of Clinton. As one Irish civilian who witnessed both presidents’ visits told The Guardian: “Clinton was charismatic, like a film star. Biden is … older.”

Thankfully, Northern Ireland is in a very different place now compared with when Clinton first visited. The peace agreement has held for 25 years despite numerous challenges along the way. It is perfectly possible that Biden’s intervention will do the trick — aided by the $6 billion of investment in the province he has promised reluctant unionists if they return to the power-sharing agreement.

Even so, it is hard not to reflect that, in addition to lacking the charisma of Clinton, Biden also does not bring the same power projection enjoyed by his presidential counterpart in the 1990s. This is not a question of personality, per se, but rather of the different global reality in which Biden operates.

While Clinton could charm the people of Northern Ireland toward a settlement as head of unquestionably the most powerful state on earth, and leader of a victorious West, Biden instead leads a divided US and a weakened West.

Clinton’s intervention was part of a wider global American agenda in the 1990s and 2000s. Successive presidents pursued a liberal global hegemony that frequently promoted its two values of neo-liberal capitalism and democracy.

Unchallenged by any serious rivals after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, this “unipolar” moment allowed Clinton to intervene in Bosnia, Sierra Leone and the Israel-Palestine peace process, though he would later be criticized for not acting to prevent the genocide in Rwanda.

Tony Blair, the former British prime minister and one of the original architects of the Good Friday Agreement, proved to be a partner in US activism after his election to the British premiership in 1997. While Clinton and Blair would later be criticized, rightly, for some aspects of their liberal interventionism, their actions reflected a period of unparalleled Western confidence, belief, and power.

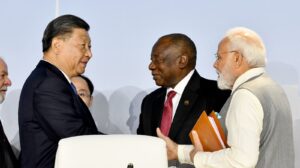

Fast forward to 2023, and Biden is not operating from the same commanding position. The US remains the most powerful state in the world but it is far from unchallenged. China is close to matching it economically, if not militarily, while Russia is more combative than it was in the 1990s.

Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine has shown the limits of Western power in today’s multipolar world. Only Western states have joined Washington’s sanctions on Russia, while almost all states in Asia, South America, Africa and the Middle East have declined to do so.

While Clinton came to Northern Ireland keen to heal Britain and Ireland’s long-running problem and to boost the Western coalition as it pursued a US-led “New World Order,” Biden’s challenge is simply keeping the fragile Western coalition together.

Indeed, Biden would be justified in feeling frustrated that he needs to intervene at all. The Northern Irish stalemate that threatens peace in the province has come about because of Brexit, a damaging goal for the Western coalition in which two of Washington’s allies, Britain and the EU, have turned on one another in mutual recrimination.

At a time when Biden would rather these key Western partners were uniting to face down shared Russian and Chinese threats, years of wrangling and recriminations over Brexit have only made the Western alliance more fractious.

Britain’s new Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has adopted a more conciliatory approach than his more anti-EU predecessors, but Biden will be well aware that Sunak himself was a leading Brexiteer and signed off on the confrontation with Brussels when he was chancellor.

Biden has welcomed Sunak as a security partner in the new anti-China AUKUS alliance between the US, the UK and Australia, but this is no Blair-Clinton or Blair-Bush partnership. Brexit has made Britain less powerful and less relevant to the US and, as a result, has weakened the Western coalition.

Of course, Brexit was not the only act of Western self-sabotage that has weakened the global position of the US and its allies. Bush and Blair’s invasion of Iraq was arguably the beginning of the decline, followed by the financial crash of 2008 and Western governments’ reactions to it.

Former President Barack Obama’s unwillingness to enforce his chemical weapons red line in Syria in 2013 damaged perceptions of American power, while the election of Donald Trump in 2016, and the divisive nature of US politics that followed also damaged American credibility. The constant news bulletins reporting on mass shootings and angry pro- and anti-Trump rallies continue to hit US soft power.

The world has moved on since Clinton’s charismatic visits to Northern Ireland, and the West is now weaker. Biden is not responsible for this, as many of the developments were before his time and/or beyond his control, but it is the reality he faces nonetheless.

As US president he might still be able to persuade recalcitrant unionists but circumstances mean he is not promoting the positive vision of the future that Clinton did. Biden’s goal is merely to hold the fragile Western order together, not sell it to the world as Clinton did.

Source : Eurasiareview