Rather than ‘shaken, not stirred’, one 17th-century Polish spy would likely ask: ‘Black or with milk?’ Jerzy Kulczycki was not only one of the very first people to open a café in Vienna, but apparently also the first person to come up with adding milk to coffee. Just how did his heroic stance during the Battle of Vienna lead him to become an internationally recognised figure in café culture?

Spying on the Grand Vizier

Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki (a.k.a. Georg Franz Kolschitzky) – a Polish nobleman, born in the town of Sambor in today’s Ukraine – led a rather eventful life as a soldier and spy. In an article, Jerzy S. Kulczycki, a Polish historian and also a relative of Jerzy Franciszek, writes:

He graduated from the Sambor parish school but doesn’t figure among those inheriting family estates, as he became a military man. It’s quite possible that he served under Jan Sobieski, the prospective king […]. He participated in Polish military interventions in Bukovina and Moldavia […]. At the time J. F. Kulczycki was already learning how to speak Vlach (Romanian), Turkish and also Hungarian.

Little is known for certain about the early stages of his life. Some claim that he was taken captive as a Polish soldier by Ottoman troops and was a prisoner of war for two years – which would explain how he came to know Turkish so well. Others object, arguing that Kulczycki was, in fact, a Serb, only posing as a Pole. This seems a rather far-fetched notion, given that Kulczycki’s Polish lineage has been personally traced back by his own historian relative.

There is no question, however, that in 1660, Kulczycki found himself in Vienna, where he arrived via Serbia. His command of Turkish and Hungarian secured him a job with the Oriental Company, an Austrian trade organisation doing business with the East, for which he worked as a translator in Belgrade. Three years later, he was already acting as an Austrian diplomatic courier and translator in Istanbul, where he also appeared in the same capacity in 1679. In the Ottoman Empire, Kulczycki was asked to spy on the Turkish military – he is even said to have had an audience with the Grand Vizier.

In 1680, Kulczycki returned to Vienna, where he presented the state authorities with a written report in which he informed them that Turkey was preparing for a war against Austria. Despite attempts being made by the Austrians to maintain peace, war broke out.

An endless sea of Turkish tents

On 13th August 1683, during the fifth week of the siege of Vienna by the great Turkish army, Kulczycki, along with his servant Jan Michałowicz, sneaked out of the city at night. They weren’t fleeing – on the contrary, Kulczycki was carrying out a secret mission for the commander of the city’s defence, Count Stahremberg, who wanted him to send out a plea for help. Dressed up as Turkish soldiers and using Kulczycki’s expert knowledge of the Turkish language and culture, the two managed to pass through the invaders’ camp unnoticed.

Here’s how the noted German writer Eberhard Happel described the passage in his 1688 book Thesaurus Exoticorum (Encyclopedia of Exotics):

When it began to dusk a little, an endless sea of Turkish tents unfolded before his eyes. The sight made him wonder which route to choose to pass through the camp. Nevertheless, he kept moving on together with his companion […] and to divert any suspicion from the minds of the Turks that were riding past them, every now and then he sang merry songs in their language.

The Poles eventually reached the chief commander of the Austrian forces, Duke of Lorraine Charles V, whom they presented with letters from Viennese officials and informed about the city’s desperate situation: the lack of ammunition and diseases spreading among the townsfolk. They also shared the intelligence about the Ottoman camp they had acquired during their journey. The two Polish messengers then returned to the besieged city, using the same ploy as before, to bring back word from the duke that rescue was on the way.

The good news boosted the morale of the fighters just enough for them to hold out until the famous Battle of Vienna on 12th September 1683, when a coalition of international forces led by Polish king Jan III Sobieski won a stunning victory against the Turks, saving the city. Kulczycki’s intel about the Turks’ positions most probably played an important part in that triumph.

Rewarded with food for camels

The Austrians rewarded Kulczycki for his courage. He received a house in Leopoldstadt and a nice sum of money. But what he wanted most, was something else entirely – after some effort on his part, he was allowed to run a coffee house. At the time, Kulczycki’s idea to open a café must’ve seemed rather odd as there were only a handful of such establishments scattered around of Europe – coffee wasn’t the popular drink it is today.

It was often even disliked for its popularity among ‘the infidels’, as shown by the following words written around 1670 by the Polish poet Jan Andrzej Morsztyn:

In Malta, I remember, we tried coffee

A drink […] for Turks, but so very nasty

A beverage like vile poison and toxins

That doesn’t let saliva pass through one’s teeth

A Christian mouth let it never sully

Since Kulczycki had been to Istanbul before the war, he must’ve discovered the local coffee culture, which was much older and far more developed than that of other European countries. The Pole had seen the potential of the steaming black beverage. There was also another key factor at play: he was in the possession of a huge amount of fresh coffee beans. The winners of the battle had seized, along with other loot from the enemy camp, numerous sacks of coffee beans the Turks had brought with them to keep themselves alert during battle. But the victors failed to recognise the beans for what they were, presuming they might be some kind of food for camels. Kulczycki, who was well aware of their worth, managed to take plenty of them for himself.

Apparently, after the victory, King Jan III Sobieski summoned him to reward him for his efforts, allowing him to take anything he pleased from the loot they had recovered. Much to the astonishment of those present, Kulczycki chose what appeared to be the near-worthless camel feed.

Opening the Blue Bottle

Equipped with the beans and the knowledge of what to do with them, Kulczycki opened the first café in Vienna. Or did he? In some sources, you’ll find that the first Viennese café was actually opened by an Armenian by the name Johannes Diodato, two years after the battle. This version of events was suggested by the Austrian historian Karl Teply at the turn of the 1980s.

Then again, the Austrian Piarist priest Gottfried Uhlich, in his 1783 book Geschichte der Zweyten Türkischen Belagerung Wiens (The History of The Second Turkish Siege of Vienna), claims that it was indeed the Pole who was first. Although this account was accused of being false by Karl Teply in 1980, it was later backed up by the findings of Jerzy S. Kulczycki, who used his family archive to research the topic and published a detailed article on it in 2007, entitled Prawdziwa Legenda Wiedeńskiej Wiktorii (The True Legend of the Viennese Victory).

What we can say for sure is that Kulczycki opened one of the very first cafés in Vienna. The fact that he opened a popular coffee house in the city is beyond any doubt. For a long time one of the houses on Singerstrasse Street was even embellished with a plaque saying ‘Here in 1683, Kulczycki opened the first coffee house in Vienna’.

His new coffee business changed addresses and it was only after some time had passed that it re-opened at 624 Schlossergasse Street under the famous name The Blue Bottle. The name was a tip of the hat to his second wife, Leopoldina Meyer. Supposedly before the two were married, she had nursed Kulczycki back to health after he had been wounded defending the city, using a medication stored in a blue bottle.

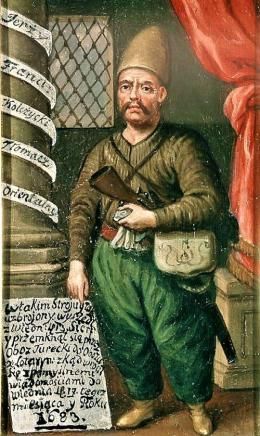

The place quickly became popular and was frequented by Viennese aristocrats such as Count Stahremberg himself. To amuse his guests, Kulczycki would greet them wearing a Turkish outfit. And to make the taste of the coffee to their liking, he would add milk and sugar – the unaltered flavour was a bit too tart for the Austrian palate. Kulczycki is considered to be the first to mix the black and white beverages and is apparently the one who invented the classic Viennese drink Wiener Melange, a coffee drink similar to the cappuccino. Some even claim that he convinced a local pastry chef to make The Blue Bottle guests special crescent-shaped rolls commemorating the victory over the Ottomans – which later evolved into the French croissant!

Despite the controversies regarding whose café was actually the first one to be established in Vienna, even the official website of the City of Vienna acknowledges Kulczycki’s contribution to the development of the city’s rich coffeehouse culture:

The history of Viennese coffee house culture is closely linked to the end of the Siege of Vienna in 1683. Legend has it that the Viennese citizen Georg Franz Kolschitzky (1640 – 1694) was the first to obtain a licence to serve coffee in the city following his heroic actions during the Siege of Vienna. The coffee beans left behind by the Turks were the basis of his success. A street in Vienna’s 4th district was named after him and a statue was put up at the corner of Favoritenstraße and Kolschitzkygasse.

Patron saint

Thanks to his wartime deeds, Kulczycki became quite famous. Understandably, this drew attention to his café, but Kulczycki was more than just a celebrity owner. He wanted his establishment to be a meeting place, rather than merely a place of consumption – a place with a pleasant atmosphere, where one could come to relax and talk, exchange thoughts and ideas.

This approach of his was why he is still considered a ‘patron saint’ of Viennese café culture. The Viennese Coffee-Makers Guild even used to have a painting showing Kulczycki receiving the privilege of running a coffee house from Emperor Leopold I as its emblem. In the Old Polish Encyclopaedia written in the years 1900-03, the renowned Polish ethnographer Zygmunt Gloger wrote about yet another form of commemorating Kulczycki’s legacy in Vienna:

Up to this day in all the coffee houses in Vienna, every October, a portrait of Kulczycki wearing a Turkish outfit is put on display, to remember him.

Over the years the format of the Viennese coffee house evolved and eventually, it became an establishment, where not only the black beverage but also warm meals were served and the patrons were provided with newspapers. Also, it became a place of intellectual and cultural discussion, where the likes of the artist Gustav Klimt or father of psychiatry Sigmund Freud would bump into each other and have a chat or listen to a concert given by a renowned classical musician. The Viennese-style café eventually became popular in the vast territories of the Austrian Empire and became a benchmark for the continental coffee house.

Today the Viennese coffee house culture figures on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage and it’s hard to find a ranking of the world’s top coffee cities which wouldn’t include the Austrian capital. And Kulczycki is an important part of this heritage. In September 2017, The Guardian published an article about an American coffee chain named after the Pole’s café in which Kulczycki is described as a ‘Viennese folk hero’. If Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki were still around, maybe he’d comment on it with a merry Turkish song…

Source: Culture