The Australian government has proudly stressed its commitment to nuclear stewardship as part of the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine plan. Responsible nuclear stewardship involves more than proper handling of nuclear materials under the oversight of the International Atomic Energy Agency, however. In fact, the riskiest and most consequential aspects of nuclear stewardship involve a part of the AUKUS plan that we’ve heard the least about: how the government intends to safely create a long-term storage facility for the military-grade nuclear waste from the nuclear-powered submarines.

While long-term nuclear waste storage involves significant technological challenges, most plans do not break down due to technical problems. Instead, a failure to obtain community consent is the largest factor in the dozens of fizzled plans globally for nuclear waste repositories. This community consent is commonly referred to as “social licence,” and includes ongoing popular and political support for, and confidence in, the technical, political and economic plans for nuclear waste storage.

Plainly put, if the Australian government does not take the immense challenges of social license seriously, it invites the negative outcome known as DADA: Decide, Announce, Defend, and Abandon. However, if it treats social license as equally important as technical plans for nuclear waste storage – including in up-front planning and resources – the government will dramatically improve the likelihood of success.

Appropriate safety for nuclear waste storage is not just a technical issue – it is also a social and political judgment to be determined by communities in a democratic society.

By taking social license seriously, the government can avoid spending taxpayer money on a process that is unlikely to succeed and can also avoid wasting precious time on building a safe, long-term storage facility that is required to protect human health and the environment.

What does social license entail? Most important, it is not a set of boxes to tick off. Rather, it involves a mindset of genuine dialogue and consultation: being willing to listen openly and to hear unpleasant and contrary perspectives. Social license is not merely educating the public. It involves deep engagement, at the end of which communities are allowed to say “no thank you”.

Social license is not something that technical personnel do to reassure emotional, uninformed members of the public. Instead, it involves an acknowledgement that what constitutes appropriate safety for nuclear waste storage is not just a technical issue – it is also a social and political judgment to be determined by communities in a democratic society.

Genuine, participatory social license processes take a great deal of time and resources, but if done properly, can build the trust required: trust not only in geological studies and technical plans, but also trust in the people and institutions managing the building and operation of a nuclear waste repository. If done right, it can create legitimacy for the project and confidence that technical challenges will be handled professionally and in consultation with the community.

In short, social license done right is expensive, takes a long time, and requires the right kind of expertise. Perhaps hardest of all, it requires planners and policymakers to be humble in the face of community engagement, rather than dismissive or arrogant.

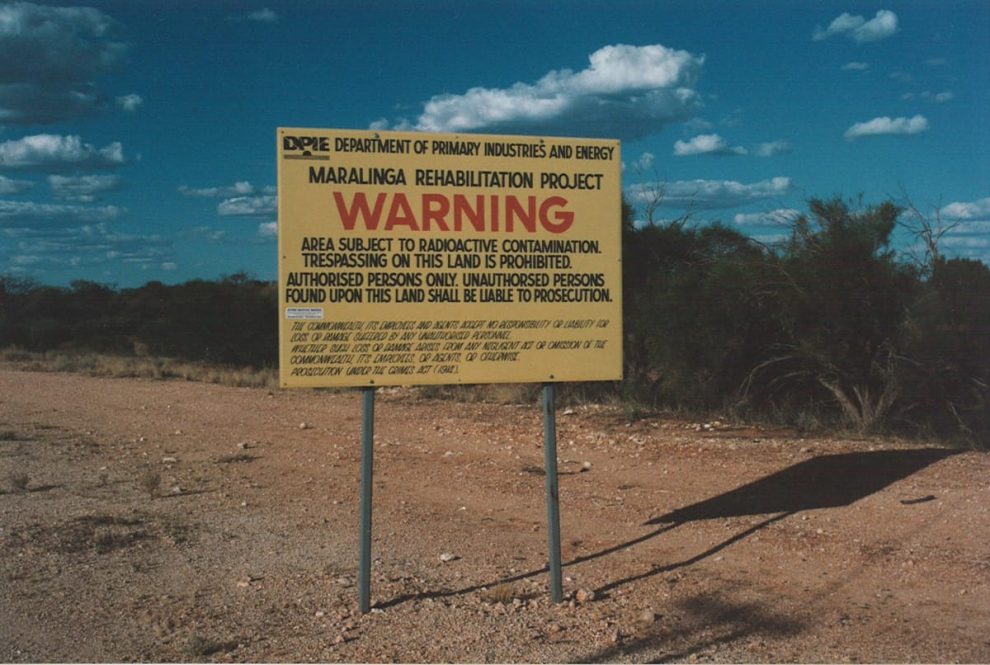

For Australia and other countries with First Nations peoples, fully including traditional owners from the start is absolutely critical to maintain any sort of legitimacy of the social license process. Consultations should embrace participation from Indigenous communities rather than exclude or sideline them. This is especially the case in Australia, where harm from nuclear activities has been borne most heavily by Aboriginal peoples, including British nuclear testing in Maralinga.

On this point, the Albanese government needs to pay close attention to the lessons of the Morrison government’s bungled proposal for a low-intermediate nuclear waste storage facility, planned for Kimba, South Australia, which is already on the road to DADA.

Although community consultation took place, including a ballot of ratepayers, traditional owners have argued they were excluded from the consultation process and were not permitted to vote, even though they are native title holders, because they do not live in council’s boundaries. Indeed, the Barngarla people asked to be included in the vote, arguing that allowing freehold people to vote while excluding native title holders seemed to infer racial discrimination. According to the chair of the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation, Jason Bilney, “if a proper heritage assessment and consultation with the Barngarla people had occurred, the dialogue could have been less combative.” Instead, the matter is now in court, and South Australian Premier Peter Malinauskas has publicly sided with the Barngarla people.

The Australian government has spent decades trying to locate a suitable site for the low-medium nuclear waste repository, but because of the Morrison government’s attempt to short circuit a responsible social license process, the Kimba facility teeters on the edge of falling over. Even if the government does manage to win through the courts, it will still have lost the larger battle of trust and confidence so critical to social licence.

Both the current government and Defence planners need to learn the lessons of Kimba – being willing to take the time to consult, including with traditional owners, in a genuine manner, even if it raises costs and extends timelines. In addition to the principles of open and humble social license, this principle of First Nations engagement must be enshrined in the government’s approach for the high-level nuclear waste repository siting. Responsible nuclear stewardship demands no less.

Source : Lowyinstitute